Humour as both a weapon and a shield: talking to Sam Elkin about his memoir 'Detachable Penis: A Queer Legal Saga'

In this very excellent book, Sam Elkin relates his bumpy journey from lesbian to transgender lawyer in the aftermath of the 2017 marriage equality postal survey.

There’s a broad and unfair stereotype about queer memoirs being trauma dumps that can be… a lot to read. In our defence, there’s a lot of trauma to work through.

But it’s quickly apparent that Sam Elkin’s new memoir Detachable Penis: A Queer Legal Saga is a very different beast from that trope. Firstly, it’s an accomplished and delightfully easy read - I whipped through it in a day, due to how compulsive I found the story. Secondly, while it never shies away from trauma - it does cover the traumatic marriage equality survey era after all - Sam also places as much focus on humour. It is at times, a very funny book.

In an unflinching tale of queer liberation, Sam Elkin offers an intimate and honest view inside the legal trans debate in Victoria, whilst grappling with personal trans debates of his own. As the inaugural lawyer of Victoria’s queer law service, Elkin is quickly immersed in thorny debates around trans inclusion in sport, children’s access to puberty blockers, birth certificate law reform and the Christian right’s demand for enhanced religious freedoms. Set against the backdrop of a growing moral panic about the “trans agenda”, Elkin reflects on the double-edged sword of visibility post the “transgender tipping point”.

I was lucky enough to have a chat to Sam about his new memoir.

PATRICK: What prompted you to write the book at this time, and about that particular time in your life?

SAM: The first kernel of the idea came from when I was conducting LGBTQ inclusive practice training sessions when I worked for the LGBTQ Legal Service. There's a scene of this in the book where I'm sort of digging up all of the sad stats on the state of the trans and gender diverse communities, a higher rate of homelessness, unemployment, stuff like that. And wondering - is any of this helping? Or is this just reinforcing, you know, the deficits in our community and seeking funding and stuff on the basis of being not okay? Is it just making us more not okay?

So, that's the way the kernel of the book came from. I wrote an essay called The Sad Steps The Trauma of Community Law, which was put out by the Griffiths Review. And that was really what started me writing the book, because the community lawyers who read it really connected with it.

Also the LGBTQ Legal Service was really my first 1,000% full time job. And I felt like I couldn't explain what happened because I was really shamed that I'd been so traumatised by the experience. I guess I just wanted to like, tell my story of what actually happened because it was sort of traumatic and funny in various parts. And I guess we just have a desire to share our experiences.

PATRICK: I was really interested and depressed by reading a lot of the depictions of how hard it is basically to work in these organisations like the legal service, and not for profits, and places that are ostensibly trying to make our community better - but all these problems come along with it. Do you think that there is a reason why there are so many issues when working in these kinds of places, and some sort of, I don't know, fundamental reason why it's not working so well?

SAM: Oh, yeah. I mean, it's underfunded. It's the short answer in a lot of different ways. Like, if I was to get a job at the Department of Public Prosecutions for example, I'd get paid like 30% more like straight off the bat - so there's a financial incentive to work for the other side right there, not to mention the financial benefit to you, right? Get work in the private sector. So that's a huge issue.

We're going into budget mode at the moment - you're seeing legal aid and other places putting out statements about why they need more money. But, you know, at the end of the day, the government doesn't fund these organisations well enough because a lot of the time we're contesting the decisions the government makes. So it's like Centrelink appeals and IRS appeals, migration law appeals. It's trying to sort of hold the government to account a lot of the time.

So that’s the very real reason why they don't necessarily want these organisations to be well-funded. So I guess that's the, you know, the big answer.

I think it's also fair to say that, any organisation that you work for that's oriented towards a traumatised, vulnerable community can end up taking on the characteristics of that trauma through secondary vicarious trauma. And by emotions going back and forth, if the people that you're speaking to are all in an elevated state and having a really shitty time, that's going to flow on to the person as well - particularly if you're passionate person that cares. And that's usually why you got into social justice in the first place.

PATRICK: Unfair follow up question to this. But, you know, is there a solution?

SAM: Well, yeah, legal aid commissions and clean legal centres should be funded much better than they are at the moment. And I think that the staff that work in these organisations should be respected more for the work that they do.

PATRICK: I really adore the humour that is in this book. It makes it a very generous read. And it also ties in with what we were saying earlier about trauma - sometimes you need some jokes to help you get through it. What is your perspective and thesis on including humour in deeply personal writing like this?

SAM: I've always found that humour has been a protective quality in my life. And I think the LGBTQ plus community for a long time is used to that too - if you think about drag queens and other queer humour, a lot of it is leaning into humour as a way to, you know, avoid the pain. It's a double edged sword, it can really help, can also help you be avoidant to what's really going on.

When I was growing up, I came across a copy of Quentin Crisp’s The Naked Civil Servant. Somehow I came across it and that was a real seminal text for me. That book’s full of humour and pithy one liners, it's also a memoir about being harassed by the cops, being spat on and laughed at by neighbours and stuff like that and being chucked out of the family home. So when you actually break it down, it's a really sad book about a lot of sad things, but it doesn't feel like that. It feels really humorous. And, you know, Quentin Crisp, for all of his shortcomings, of which there are many, made an absolute killing in a literary sense of turning pain into humour. And I think it was used as both weapon and a shield. Yeah, I'm really inspired by that.

PATRICK: I really like how you placed side by side with your own personal experience - transitioning and personal events - with the broader context of the queer and trans rights battles happening at that time, around the marriage equality survey era.

SAM: I guess the experience of transitioning was so bound up in my experience of engaging in all that. It really felt like transgender rights was just like in the media constantly. You know, you had Scott Morrison talking about gender whisperers and saying that the Prime Minister's office had to take down a gender neutral toilet sign in his like first fortnight in office or something like that. And that was really when I just started transitioning. Not that I thought me and Scotty were going to be like best mates, but it's pretty confronting having your head of state denigrating your kind. Like it's basically his first order of business.

So yeah, I just felt like my experience of transitioning was bound up in that - I wasn't trying to make a sort of complex intellectual argument or whatever. That was what it was, what I was going through my mental health appointments to try and get my letter, to try and get approval, to get surgery while I was reading these inflammatory tweets that the Prime Minister was putting out or articles in the paper about the Australian Christian lobby and what their plans were for rolling back marriage equality. This is just what was going on in the closet at the time. So it felt like it wouldn't be an honest depiction of my life if I didn't talk about that.

—

Sam Elkin is a writer, event producer and co-editor of Nothing to Hide: Voices of Trans and Gender Diverse Australia (Allen & Unwin, 2022). Born in England and raised on Noongar land, Sam now lives on unceded Wurundjeri land. Sam’s essays have been published in the Griffith Review, Australian Book Review, Sydney Review of Books and Kill Your Darlings. He hosts the 3RRR radio show Queer View Mirror and is a Tilde Film Festival board member. Detachable Penis: A Queer Legal Saga is his first book.

Thanks for this interview with Sam Elkins. I'll definitely be buying his book! I was pleased that the first question hit on the real problem with the "Trans trauma narrative" as it was then - and still is today. Not that being Trans has a lot of difficulty (and trauma) often associated with it, but many voices and even commissioned reports often stated ONLY the trauma that Trans people experienced and hardly ever the good that occured in our lives. Unsurprisingly, that one sided narrative was weaponised by the Right, casting being Trans as THE CAUSE of our traumatic experiences. I first published on that problem back in the late 20-teens (see my pieces in Archer), but it has been a real effort for those of us in the advocacy space to nuance the Trans narrative so that the causes of BOTH our liberation and repression can be better understood in the public space. When you do that, it's easy to explain to non-trans people what our needs are. And, surprise, surprise! Our needs (for health, housing, legal, finacial access) are more or less THE SAME as everybody else's. Trans people aren't sad, broken, alienated people needing to be "fixed", we are people Just Like You, who simply want to be treated fairly.

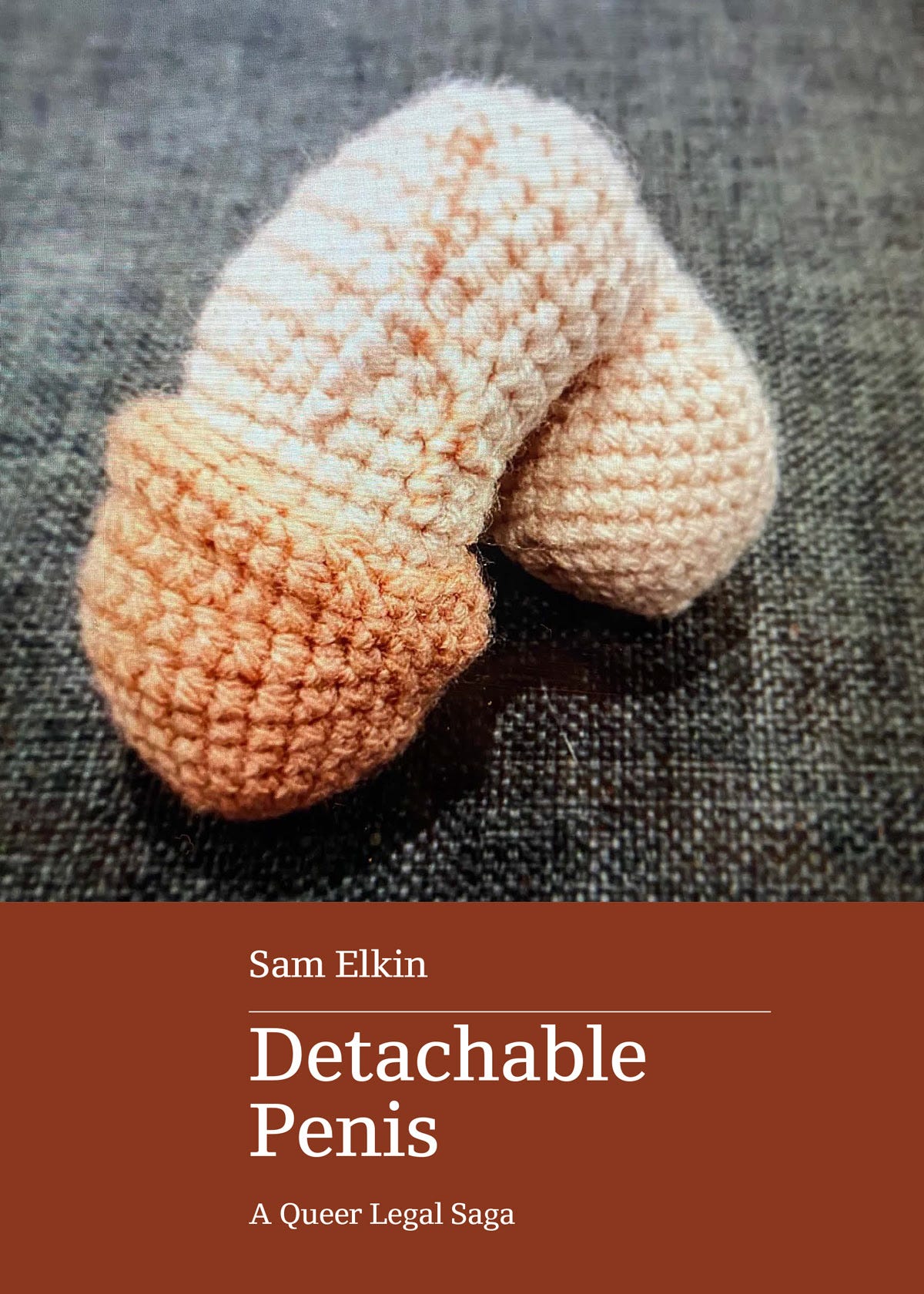

Great interview! So glad you shared this with us. I think I need this book, and the cover is brilliant!