I'm a gay author, and schools are still asking me to "skip over" the queer parts of my books and my life

I've been an author for fifteen years, I want it to feel like less of a struggle.

2016. Dymocks George Street.

There's something about a book launch that turns my brain to mush. I flit about anxiously, forgetting names, conversations, the fact I really should have addressed the tiny crowd by now...

A launch is the culmination of years of hard work, an opportunity to ply friends and family with finger food and whatever alcohol Dan Murphy's had on special, in the hopes they buy a copy or two.

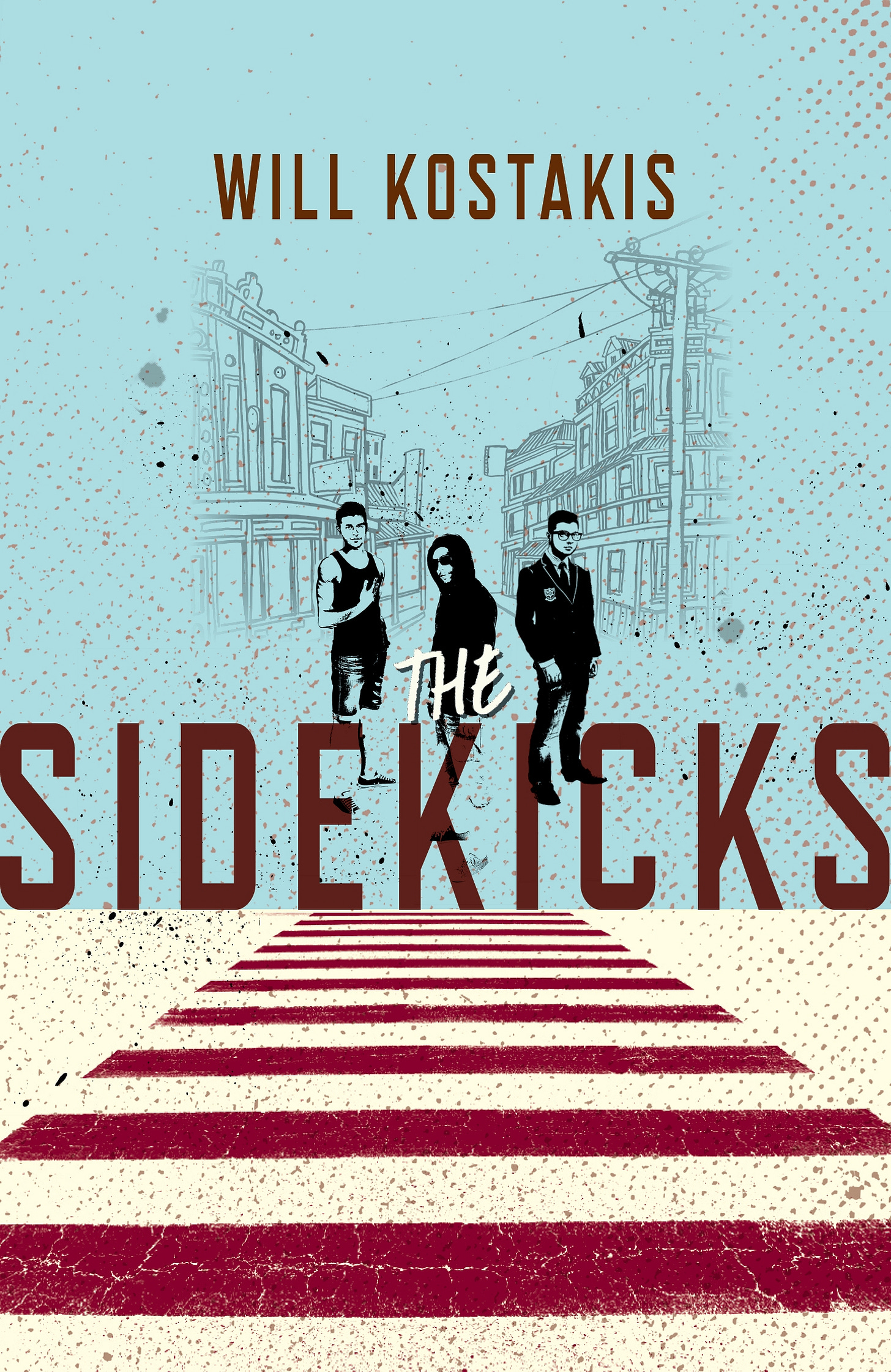

Tonight I'm flogging The Sidekicks, and I'm especially flitty, especially anxious, and especially forgetful. I have just come out. I always imagined myself most comfortable with a gentle, quiet, leave-it-mostly-unsaid kind of coming out. I mean, I'm the middle of three gay sons. Everything my mother touches turns to gay. My homosexuality is a non-event.

I tried gently, quietly telling friends and family, leaving my sexuality mostly unsaid in a blog post (remember those?!), but as of a couple of hours ago, the Sydney Morning Herald homepage has run the words "gay author" above the horniest picture of me imaginable. I'm bouncing between people sipping plastic cups of discount wine, and they're alternating between telling me they're proud, and telling me they're sorry this has happened to me.

A Catholic school cancelled one of my gigs after my leave-it-mostly-unsaid blog post could've said a little less.

And even though my mushy brain keeps me from remembering book launch specifics, there's one part of that night I keep reliving: a publisher pulls me aside and tells me not to make it all I am. Being gay, that is.

Each time I relive it, I read her comment differently. At first:

She was homophobic.

Then:

No, she didn't want me pigeon-holed, writing the same gay, angsty coming-out stories over and over.

Actually:

Oh, she was worried about the bottom line. Literary young adult fiction depends on the schools market, so a certain hyper-vigilance about appropriateness is required to ensure queer themes don't keep a book from being studied (and ultimately, making bank, or at the very least, returning a profit).

But as attitudes towards queerness have shifted over the years, I've settled on:

She was worried about nothing.

I've seen booksellers scramble to reorder copies of Heartstopper to keep up with reader demand, and visited Catholic schools working tirelessly to establish support networks for their queer and questioning students. Sure, there's been an industry-wide fixation on (often traumatic) coming-out narratives that don't allow their queer protagonists to be themselves or experience joy for large chunks of the story, but that's me nit-picking. This is all progress. And I expect progress to keep progressing.

—

2023. A different bookstore, 500 kilometres north.

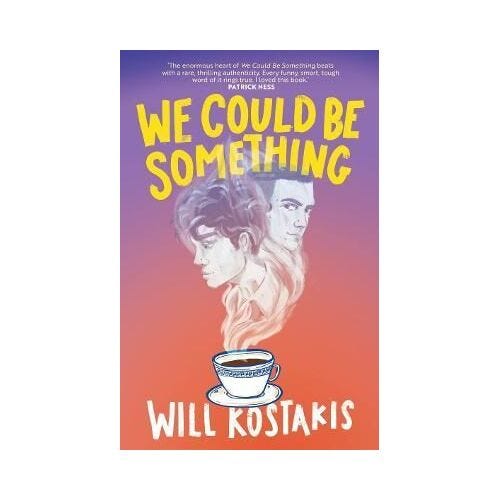

A Catholic high school teacher reaches for my new release, We Could Be Something, a sprawling (yet intimate) portrait of a Greek family in crisis, ideal for years ten and above. She's refreshing her text list, so she gives my blurb a crack. She gets fewer than three words in.

It says coming out. There’s no way the school can make it work.

She places We Could Be Something back, dismissing three years of work in an instant.

To be a queer author in 2023 is to experience near-constant whiplash.

There’s the rush of finding out teens at your all-boys high school now study the gay coming-of-age novel Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe … and then another library drag storytime event is cancelled in response to intimidation and threats of violence.

There’s the thrill of Pride displays, permanent (and prominent) LGBTQIA+ sections in commercial bookstore chains, queer bestsellers … and the reality that one complaint from a conservative activist can pull a queer memoir like Maia Kobabe's Gender Queer from shelves (it is now only available in Australian stores because Sydney retailer, Kinokuniya paid to have it classified), and one deranged TikTok campaign can inspire a retailer to voluntarily pull an age-appropriate sex-ed resource (Dr Melissa Kang and Yumi Stynes' Welcome to Sex).

So much has changed this year that the upcoming reprint of We Could Be Something (first released in May) will feature a 'Contains Mature Content' warning on the cover. Yeah, nothing makes dicks harder than a family grappling with its matriarch's Alzheimer's diagnosis.

Just this week, All Saints Catholic College in Liverpool enquired about booking me for August 2024. August is Book Week, the busiest time for authors. The school wanted two sessions, for a total of 1200 students. One physio appointment later, I expect an email confirming the date. Instead, my agent messages to say the school has asked "if it's possible skip over the same sex components when discussing his story and books".

And again, I relive the gentle, quiet, leave-it-mostly-unsaid kind of homosexual being told not to make being gay all he is.

By now, I've accepted that publisher was wise. She foresaw an eternity of me justifying my worth, my appropriateness... No matter how much the industry changes, how much room is made for queerer stories written by confidently queer authors, and how successful those stories are, there will always be someone who thinks I'm out to corrupt kids.

I take a deep breath, and sit on the park bench outside my physio. I try another breath, doesn't do shit. I want to hurl my frustrations at them. I've done everything by the book. I've contorted around syllabi and rubric. I've taught a class on Romanticism with one hour's notice just because a teacher asked, for fuck's sake. My reputation precedes me and it's a sterling one. I want to tell them to piss off, and I do eventually, politely, but I try a Hail Mary first. I rely on the rubric I know by heart.

Texts and Human Experiences. The common module most year twelve students in New South Wales are working towards. I thumb my response into my phone:

“I have explored the many different facets of identity in my books for over fifteen years. As educators, we encourage students to regard an author's context and consider how that context affects their writing. Being gay, much like being Greek, is a vital piece of who I am and it informs what I write. I find it deeply disrespectful, fifteen years into my career, to be asked that I 'skip over' it (I think 'hide' is a more honest word).

I am assuming I have been invited because somebody on staff read my books. Imagine, then, The First Third without Sticks/Lucas. Or imagine The Sidekicks without Ryan's journey to self-acceptance. Or my latest release, We Could Be Something without ... Well, without most of it. Now imagine what your request is asking me to do to myself.

I speak to dozens of religiously affiliated schools every year – each with queer staff and queer students who appreciate my perspective. If All Saints is different, and a passing reference to the fact that I'm engaged to a man is too controversial, I'm certain that there are plenty of suitably heterosexual authors who are available for Book Week.”

Days later, it's confirmed they've rescinded their invitation.

I go public, and now it's as if eight years haven't passed. Almost every message from a friend is one of condolence. They're all so sorry this happened to me. And while I appreciate the sentiment, I resent it. I don't want to be an object of pity. I've been an author for fifteen years, I want it to feel like less of a struggle. And I want things to change, not just for me and queer authors like me, but for all the LGBTQIA+ folks who hit this wall day after day.

I want Catholic organisations to grow up and stop acting like erecting faggot-proof fences has a place in this century. And I want our governments to finally pass the legislation they've been teasing that eradicates, or hell, even slightly diminishes, religious organisations' right to discriminate on the basis of sexuality.

I don't want to be back here in another eight years. That might just break me.

—

Will Kostakis is an award-winning author for young adults, and those who love to read about them. He, like half the gays in Sydney under the age of forty, also worked a journalist for five minutes.