The long kiss goodbye: a loving tribute to the short films of Australian queer rights pioneer Stephen Cummins

A chat with film academic, queer activist and form-shredding musician Simon Hunt/ Pauline Pantsdown on the films of Stephen Cummins

Film academic, queer activist and form-shredding musician Simon Hunt – AKA satirical political firebrand Pauline Pantsdown – first met game-changing shorts director Stephen Cummins in Berlin around 1986. “I thought that he was German because he had dyed blond hair, which every second man in Berlin had then,” Hunt chuckles.

Hunt, A Sydneysider, was living in Berlin then, gigging with experimental band Bring Philip and collaborating with the Berlin Philharmonic. “Stephen was passing through with a curation of Australian Super 8 films,” he recalls. “He was a very organised person who could put together a program, including his own films, of course, then get a government grant to take them around the world to Super 8 festivals.”

Cummins, a leading light of Australia’s New Queer Cinema movement, was a consummate collaborator who thrived off working alongside fellow creatives who were passionate about social progress and cross-disciplinary creativity. He and Hunt hit it off immediately, enduring the then tortuous Checkpoint Charlie crossing in search of East Berlin gay bars that didn’t quite live up to the hype they’d fomented between them.

Hunt worked intimately with Cummins across his shorts and has become the custodian of his legacy since the filmmakers’ death of AIDS-related lymphoma in 1994. Working closely with the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA), Hunt helped them lovingly restore all nine existing works screening as part of a retrospective at the Melbourne International Film Festival on Friday, August 23, marking the 30th anniversary of Cummins’ passing.

“It’s wonderful that the NFSA came on board and saw this as an important part of Australian film history,” Hunt says.

Creating empathy

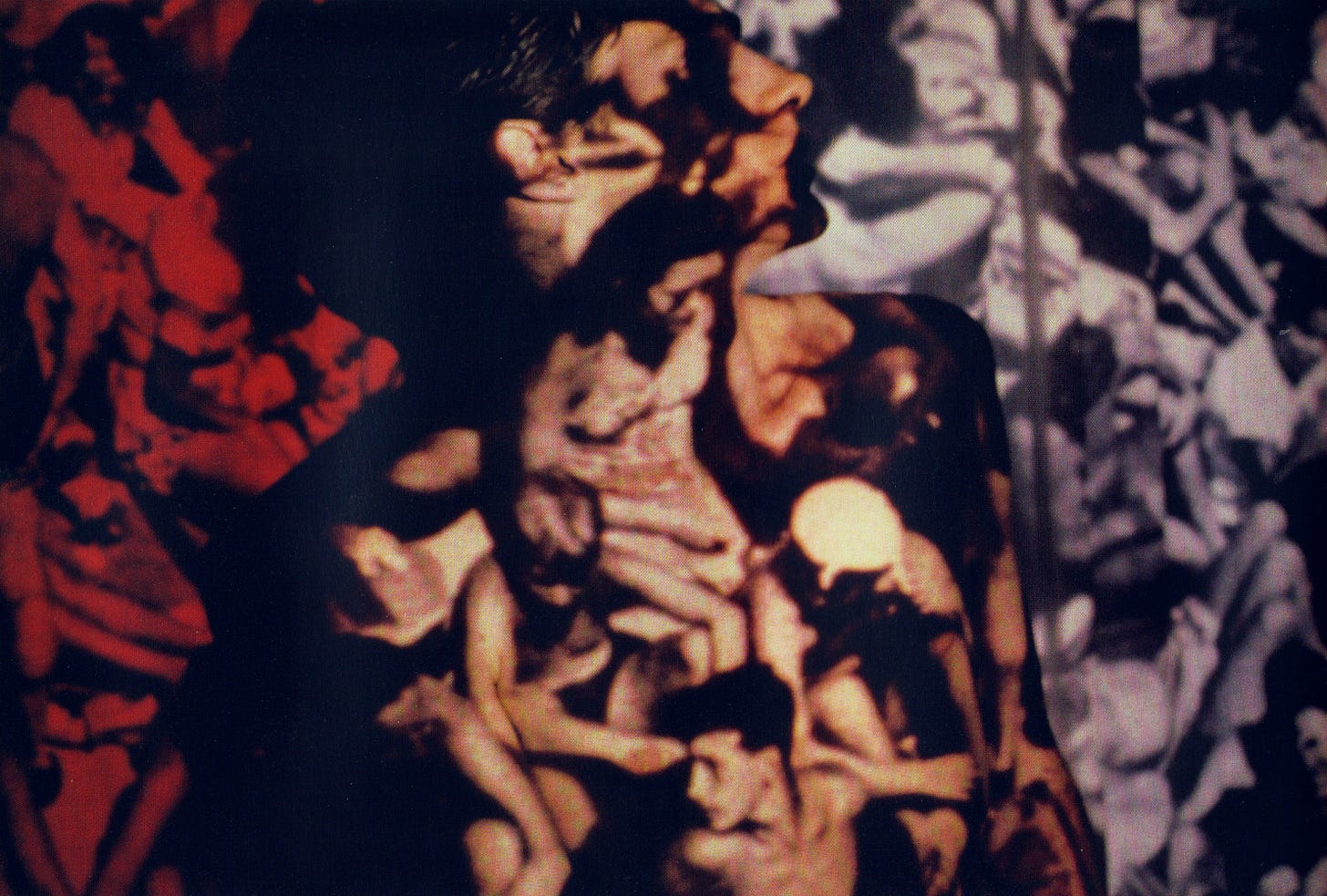

The collection includes the beautifully composed and powerfully provocative film Resonance (1991), which Hunt wrote. It opens with an unforgettable sequence, essentially putting the audience in the place of a gay man who is bashed on the street, as drawn from a traumatic real-life experience of Cummins’ and tracing the ramifications of the attack both for the victim and through those in the orbit of the attacker.

“There’s such horror in that film that, expressing the resonance of the act of that act of violence, but also healing from it and other forms of oppression, so it’s important the film looked beautiful,” Hunt says. “The sound mix is such that the violence came from the back of the cinema straight towards the screen, so it actually passed through the audience as it was happening. It was very much about ‘You are here, and this is happening to you’.”

Handsomely funded by the then Australian Film Commission, screening at over 100 festivals – including Sundance and Toronto – and winning awards, Resonance marks a structural and societal shift towards embracing queer cinema more. “They had been giving a million short filmmakers 20 bucks each, or whatever, and then suddenly they funded ten short films as if they’re a feature,” Hunt recalls. “Brendan Young, the cinematographer, did a beautiful job.”

“Stephen was never an autocratic director,” Hunt says. “He had very strong concepts, but he would bring people in from different fields. There are no actors in any of his films. They were very much the artistic community in Sydney at the time, in the experimental performance scene and the contemporary dance space.

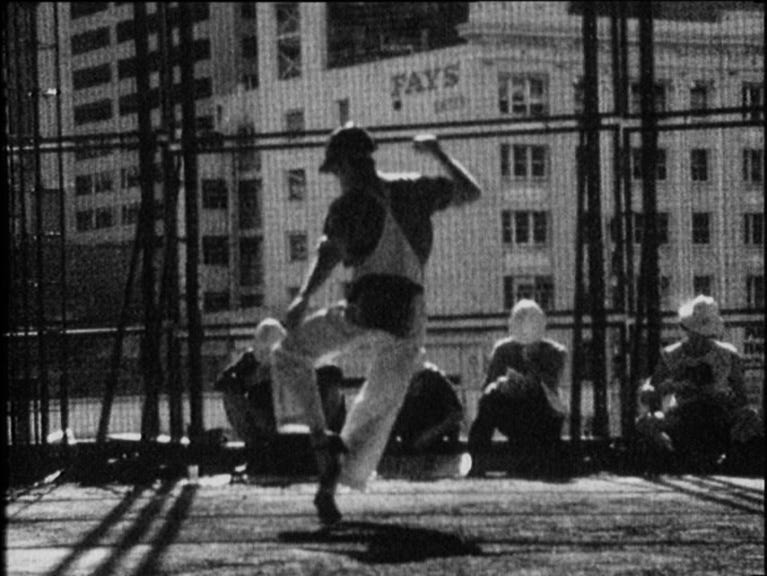

Featuring dancers Mathew Bergan, Chad Courtney and Annette Evans, Resonance shimmers with visceral choreography, a common trait in Cummins’ work, including Le Corps Imagé (1987) and the Sydney World Square construction site setting of Body Corporate (1993), written and choreographed by Bergan, who also performs.

Too hot to handle

Cummins films are also erotically charged, so much so two films were censored. Taste the Difference (1989), depicting a gay kiss in close-up, responded to a call-out for Super 8 filmmakers to craft 30-second films to run in ad breaks in WA during late-night television slots at the height of that state’s decriminalisation debate. “The Federal advertising body cleared it as suitable, then the station manager was the one who banned it, saying it’s not because it’s two men kissing, but because it’s such an explicit kiss.”

The HIV Game Show (1995) contains a snippet of Taste the Difference, framing the reason for its banning as a question for contestants. Ironically, it would suffer the same fate. “Filmmaker Lynette Wallworth, now a famous installation artist, ran a similar project where artists were asked to create a slideshow that would screen before films,” Hunt recalls.

Cinema advertising company Pearl & Dean had other ideas. “They again said the kiss was too explicit and banned it.”

Hunt had the last laugh. “We had this bloody challenging fight that went on for months, trying to overturn it,” he says. “Immediately afterwards, the classification board was reviewing censorship rules in Australia and asked for submissions.”

At the time, homosexuality was lumped in the ‘adult themes’ category along with drug use. “I rang up the chief censor and asked him if they treat homosexuality and heterosexuality differently in there,” Hunt says. “He goes, ‘Oh no, it’s our mantra not to do that’.”

When Hunt pointed out the hypocrisy, the censor agreed he had a point, and it led to homosexuality being removed as a trigger. “So that was a positive adventure that came out of the censorship of Stephen’s work.”

Lasting legacy

The NFSA-supported retrospective screening at MIFF, which Hunt and Bergan will attend, and a subsequent berth at WA’s CinefestOZ Film Festival – having already played the Mardi Gras Film Festival – is a testament to Cummins’ legacy.

“Six months after Stephen died, along came the drugs that enabled most of the HIV-positive people who I knew at the time to still be around now,” Hunt sighs. “That makes me very sad, but I’m really happy that his work is still getting out there.”

Cummins was a true champion of equality, with Hunt noting there’s still so much to fight for, particularly against the ramping up of ugly attacks on the trans community from both outside and, more disappointingly, within the queer community.

“There are forces on the far right trying to peel you off, and you shouldn’t be, because then you’ll also be discarded,” Hunt says. “The links between the different facets of Christians and Nazis and the gender criticals, who all quote the same material, become much clearer. It’s an attempt to split us, but sharing a bit of a queer history is very helpful. Intersectionality goes back a long time, so don’t fall for it.”

The Stephen Cummins Retrospective screens at MIFF on August 23 and CinefestOZ on September 8.

Stephen A Russell is a Melbourne-based arts writer. His writing regularly appears in Fairfax publications, SBS online, Flicks, Time Out, The Saturday Paper, The Big Issue and Metro magazine.

The LGBTQIA+ Media Watch Project is partially funded by The Walkley Foundation, and proudly pays queer writers, journalists and experts to write about LGBTQIA+ representation in media and culture. To support writer-owned, independent, queer-led media, please consider subscribing - this is how we pay our writers!

I had the good luck to actually have a boozy lunch with Stephen Cummins and his boyfriend (who was or is the brother of my first partner's next one). Unfortunately at the time I didn't know about his work, and was generally insufferable like I usually was in the 80s... but since then I've learned to appreciate the achievement he made. Rest in creativity!