“To write well you need to read, and read widely”: Charlee Brooks aka Grandpa’s Book Club on the internet, queer literature and his undying love for Patti Smith.

“My whole life is obviously influenced by what I’m reading and consuming, everything is to do with books.”

In the background of the voice notes that Charlee Brooks has sent me, I can hear quiet birdlike chatter, the rolling of wheels on tracks and the metallic sound of loudspeaker announcements. He’s on a train, coasting through small towns in Europe on his way to Amsterdam. He apologises for the noise.

Though he’s currently focusing on Youtube and longer form content, I first came across Charlee on TikTok. The (ever mysterious) algorithm knew that I wanted quality book recommendations and reviews, and it certainly delivered.

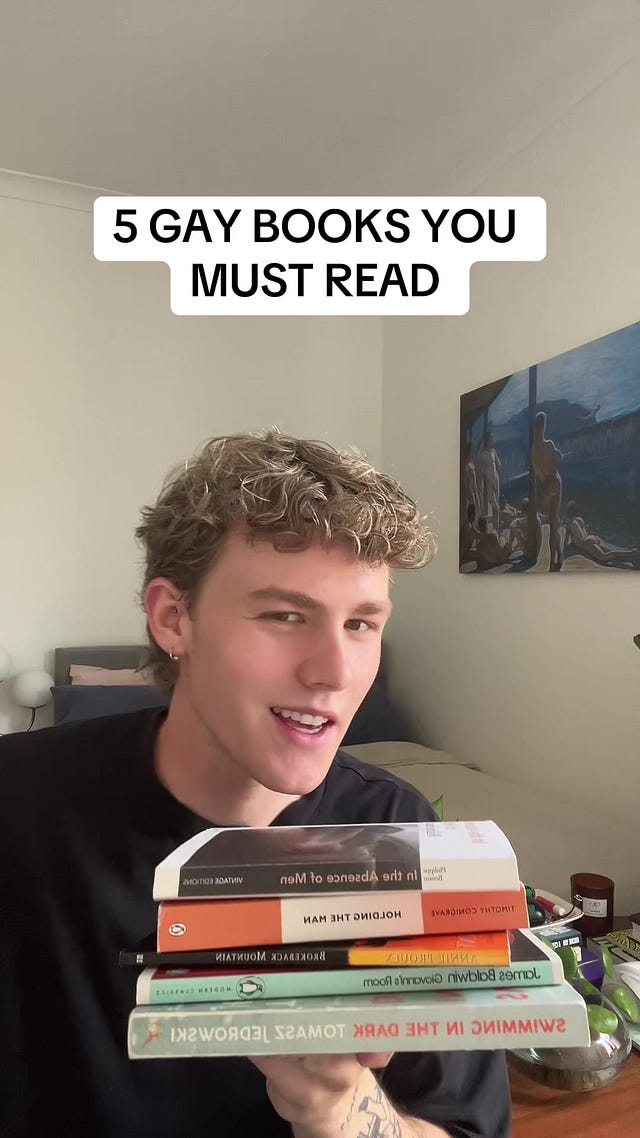

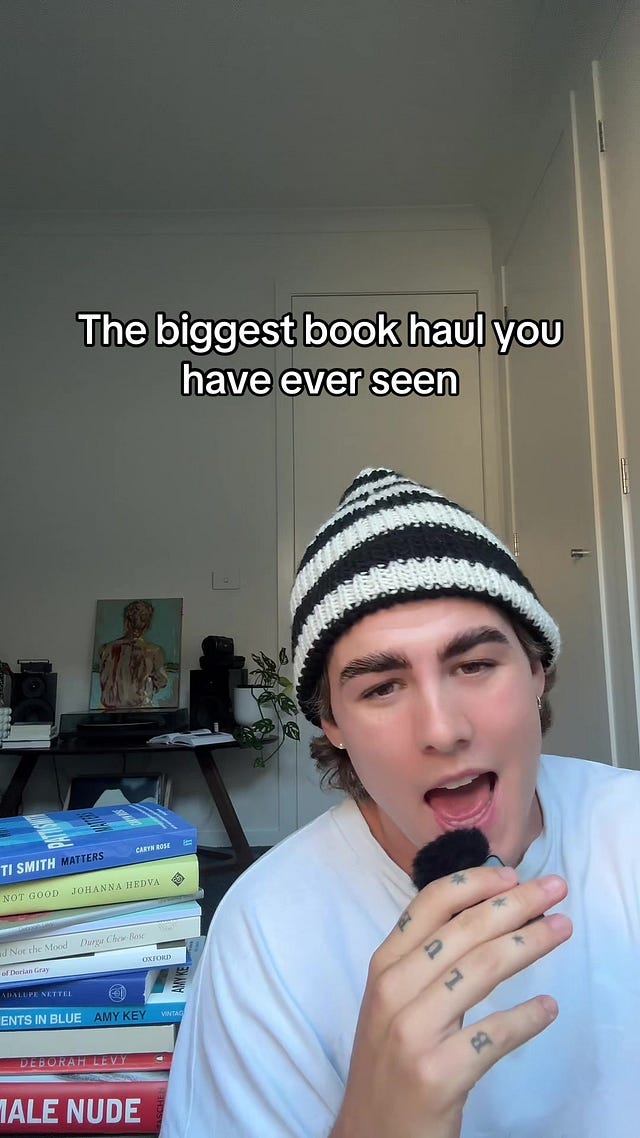

Hailing from the Victorian coastal town of Torquay, approximately 1.5 hours from Melbourne, Charlee’s content understandably has that soft, sleepy quality you might associate with an off-season beach holiday. Authentic, simple and pared-back, his quiet straight-to-camera style is a welcome antidote to the overstimulating chaos that BookTok can often become. Ever sensitive and thoughtful, his content about queer books and authors captured my attention immediately.

A paramedic by trade, in his spare time twenty-two year old Charlee Brooks is a lot of things: Youtuber, Booktoker, reader, poet, the list goes on. His content, which comprises reviews, recommendations, rants about Patti Smith, book hauls and book-related outings and vlogs, is compassionate, slow-paced and refreshing.

BookTok, a subgenre of TikTok, tends to be flooded by American and British creators, and it’s refreshing to see an Australian perspective, especially a young one unmarred by the publishing industry or having studied literature. Charlee is for the “everyman”. Watching him talk about books is like taking a breath of crisp morning air.

What came as a surprise to me as I listened to Charlee talk about his upbringing was that he hasn’t always been a reader: “I didn’t really start reading until first year uni.” A bookish person myself (as much as a hate the twee-ness of the word “bookish”), I thought that all of us grew up reading under the bed covers with a torch, or spending winter Sundays curled up in front of the electric heater ravenously reading the last few chapters of Breaking Dawn. Charlee’s later-in-life literary awakening was two-pronged: “I read Call Me By Your Name, and that was sort of my gay awakening, and from there on I just fell full force into trying to accept myself.”

There’s certainly something magical about Aciman’s novel, because I too adored it before I realised I was queer. I remember lying in a hot bath listening to the audiobook, Armie Hammer reading out that scene through my speaker, hoping to god that my housemate couldn’t hear it through the wall.

“I also read Billy Elliott” he tells me, laughing. “Liking that a little too much maybe was a sign… that maybe there was something a little fruity going on.” It reminds me of how I perhaps liked Stick It a little too much in primary school.

I’m always interested in why people start reading, and Charlee’s reason is a common one: “I wanted to get away from what I was studying.” I can relate; I remember procrastinating during my undergraduate degree by reading the entirety of the Outlander series (nine whole books if you’re wondering). “Towards third year I was completely absorbed by books and the bookish community.”

Discovering literature and then taking the leap and posting about it online seem two very different things, so I ask Charlie what made him want to delve into the wide world of the internet. As it turns out, his sister has quite the following on TikTok (I immediately picked up my phone and found her page, and I already followed her - small world). “She definitely urged me to post, and…made it a safe space to post.”

Despite TikTok’s meteoric growth in the last few years, making engaging content is deceivingly hard. A lover of Videostar and iMovie when he was younger, making videos came quite naturally to Charlee. There are 35.9 million posts (and counting) under the booktok hashtag, and I can think of only a handful of creators that resonate with me as much as Charlee does. Remarkably, he tells me he really only started posting for something to do, “then it sort of just ended up where it is and I’m still doing it and I love it and I’m very lucky that people resonate with it…I’ve really been able to gain confidence in myself and other people through talking about these stories.”

There’s something circular there, where queer stories are something for him to confide in, and they also provide the gift of community. It’s about the inner and the outer, the multiple parts that make up the whole.

Of course, online book discourse is (unfortunately) not all sunshine and rainbows. Intrigued by Charlee’s thoughts on the tricky beast that is the internet, especially since making content about queer books can be a lightning rod for homophobia, intolerance, and honestly, plain stupidity, we chat about how TikTok can quite easily devolve into what is basically a toxic wasteland of opinions and algorithms. “My videos get flagged…because I’m talking about queer subjects…There’s nothing explicit in them whatsoever but because they’re queer they get reported and TikTok takes them down.”

He says that people also tend to be quite quick to assume. They “judge and jump on…and put their opinions out there” where they aren’t necessarily welcome. Although TikTok is where most of Charlee’s influence lies and where has built his community, because of the toxicity of the platform he’s started posting a lot more on Youtube, where he can speak more directly to a dedicated (and kinder) audience.

A hot topic online for a while, and one he’s explored in his content before, I was keen to delve into Charlee’s ideas on non-queer authors writing queer characters and stories. Emphatically, he tells me that “historically in art… people need to tell other’s stories sometimes for them to be heard.” I have to agree. Surely we can’t expect queer people, especially those who have experienced trauma related to their identity, to write about that trauma purely for the benefit of those who want to read about it.

“I think it’s very narrow minded to say ‘well you’re not queer so you have no right to tell a story about a queer person’,” he says. He also highlights the importance of separating someone’s work from their personal life: “we don’t know everything that goes on in one person’s life and I think that idea of separating art from the artist is very very important.”

I bring up the example of A Little Life, a queer tragedy of epic proportions (if you know you know) written by American novelist Hanya Yanagihara, who herself is not queer. Online discourse around the book has been frustrating. Charlee zones in on one of the most discouraging things about the internet: how quick people are to jump behind a misguided cause. “People are very quick to judge…and box things in as trauma porn this and trauma porn that, and jump on authors’ backs and boycott things and cancel people.”

Charlee describes A Little Life as an “exquisitely written book… [and] very intentional.” He goes on: “just because something is traumatic or it deals with taboo or hard to navigate topics doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be written at all.”

On the prevalence of stories about queer suffering more generally, Charlee says that yes, reading it can be confronting and upsetting, “but it’s the harsh reality.” Refreshingly, he says that “to turn a blind eye and say I don’t want to read any of this because it’s so sad and makes me feel horrible, well [those] were the things that our community had to deal with.” He finds value in the sad stories, value in terms of the historical significance and in the power that is taken back by the writing of them.

As a reader who becomes very invested in whatever book is currently on my nightstand, I find myself walking through the world slightly differently with every story I consume, and I’m relieved to find that that the same is true for Charlee: “My whole life is obviously influenced by what I’m reading and consuming, everything is to do with books.”

Whether I’m reading a Diana Reid novel and find myself glamorising the plight of the middle-class uni student, or I’m absorbed in Eliza Clark’s Penance and reliving my Tumblr years, I see the way I think about my life warping, and the way I write morphing, as I read. Charlee explains that he finds himself going down literary rabbit holes too, which is a comfort to me. “My life becomes consumed by whatever the period [the book] is set in…I am very obsessive too…once I find [an author] I like I really lean into it.”

I ask him if any authors in particular inspire him, and in true bibliophile style, Charlee has a hard time narrowing down his list. I provide him with an example of my own (Hannah Kent, Australian author of queer historical novel Devotion, and possibly my favourite author of all time), though I soon learn that I didn’t need to. He offers a few of his favourites: Phillipe Eson, Olga Ravn, Rachel Cusk, Deborah Levy, Joan Didion, but for Charlee, it all comes down to Patti Smith.

“She is my life,” he says, “The light of my life.” I can do nothing in this moment but admire his passion. “I love the way she writes, she’s so honest…I’ve read almost every book she’s put out. It’s my goal to get every book in her collection.” He also speaks adoringly of the work of Patti’s best friend and former partner Robert Maplethorpe, a queer photographer who passed away due to HIV-related illness in 1989. His voice lights up as he tells me of the queer themes in Patti’s work, and that she’s still very much working in the literary space: “She’s very active in the community as well…it’s so rare to get that from someone of her age… with so much life experience.”

“I could rave about her every day,” he says, and I believe him. “If you haven’t read any Patti Smith I implore you to do so.”

The last question I have for Charlee is about his writing. I start by asking the obvious: asking him what he writes about (a somehow simple yet very intimate question). “Lots of different things,” he tells me. “I write everyday in a journal,” he says, and a pang of envy shoots through my heart; I never seem to be able to keep a journal for more than a few months. “I do wax and wane,” he adds, but when he’s feeling inspired he writes a lot of poetry. In fact, he’s got close to a full collection, which he is very keen on getting published.

“I’ve also started writing my first piece of fiction,” he continues, “which is obviously very early days but I find that I’ve been inspired by growing up in Victoria and the people I’ve begun to surround myself with in my early adult life.”

In terms of inspiration, Charlee leans on the work of the authors he loves, as we are all wont to do, but warns against falling into the trap of replication. “I definitely find myself taking bits from what I’m reading which is…a dangerous trap,” and a trap that I absolutely fell into when I first started writing.

Someone needs to tell younger me that the only person who can write like Sally Rooney is (spoiler alert) Sally Rooney. He tells me that to write well, you have to lean into your own voice, and that voice comes from reading. He tells me that above all, what he doesn’t understand is writers who don’t read. Read, read, read. “To write well you need to read, and read widely,” he says.

—

Julia is a writer living in Melbourne, Australia. She spends a lot of time in her local bookstore, plucking her eyebrows, and putting stickers on things.

As well as creating content on social media, Charlee runs his own online book club through Bindery and Discord, where members can read along with him and then engage in discussion at the end of each month.

You can find Charlee on TikTok here, Instagram here and on Youtube here.

—

The LGBTQIA+ Media Watch Project is partially funded by The Walkley Foundation, and proudly pays queer writers, journalists and experts to write about LGBTQIA+ representation in media and culture. To support writer-owned, independent, queer-led media, please consider subscribing - this is how we pay our writers!