"A crime of passion": In the wake of Jesse Baird and Luke Davis’s tragic deaths, let's discuss why the language the media used matters

Public discussion in the wake of the murders of two gay men, allegedly by a police officer, highlights the power of language to support, or undermine, efforts to end violence, according to Joe Ball.

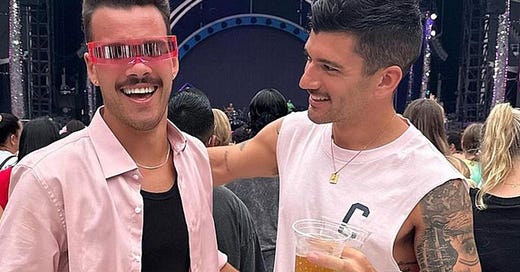

I want to start by expressing profound grief and sadness at the loss of Jesse Baird and Luke Davis, and extends my sincere condolences to their loved ones, families, chosen families and all who had them in their lives.

I stand in solidarity and devastation with the wider LGBTIQA+ communities in the face of such tragic loss of life.

I have been disappointed, pained and frustrated to witness the sensationalising and in some cases incorrect reporting of these devastating events.

This was not “a crime of passion” as the NSW Police Commissioner initially stated and has now retracted.

This crime was an act of extreme and lethal violence.

What language did the media use?

Extensive work has been done within the family violence sector on the importance of language that accurately portrays the facts surrounding acts of gender-based violence. Gender-based violence includes domestic and family violence and sexual assault, and LGBTIQA+ communities are not exempt from this.

The naming of any family violence murder as “a crime of passion” reeks of the once legal gay panic defence “I couldn’t help myself”, and of the haunting exclamation from many a person enacting violence of “look what you made me do”.

On the question of language, moments like this create flash points for us all to go on learning journey and to build new alliances to end violence.

For example, I know there are people in the LGBTIQA+ community for whom these murders are their first significant exposure to conversations around the work of preventing gender-based violence. To these people I offer some consideration around how we refer to all involved in this crime.

Increasingly language is shifting away from the perpetrator/victim binary and towards “people who use violence” and those “who experience violence”.

This language is to importantly challenge the expectation that someone who acts violently is fixed within the identity of being someone who is a perpetrator and to instead open up non polarising and non-stigmatising spaces for people to seek help if they are using violence.

If we are to stop violence before it happens, we need to work with those who use violence to change and challenge the behaviours and the contexts that support their behaviours. This is why the language “people who use violence” is used, to destigmatise a person who is seeking help around their behaviours.

One example of the help that can be sought in LGBTIQ+ communities can be seen in the Thorne Harbour Health Gay and Bisexual men’s behaviour change program, Revisioning.

If anyone identifies harmful and violent behaviours in their own lives, including stalking, harassing and not accepting “no”, I strongly encourage them to reach out to the many behaviour change programs available and that can be found through the organisation No to Violence.

We should all play a role in preventing family violence, and purposeful language in reporting and speaking on these issues helps build awareness and understanding of the drivers of gender-based violence and what ultimately needs to be done to address it.

Gender-based violence is about control and power, and is rooted in harmful stereotypes and systemic structures of power.

Family violence happens in every part of society. IBACS 2023 review into police conduct and family violence states that “Despite efforts undertaken over recent years, predatory behaviour persists within Victoria Police and remains under-reported”.

Tragic thread

I wish to recognise and respect the Mardi Gras Board’s initial decision to request that police do not march in the 2024 Mardi Gras parade. Mardi Gras is an autonomous organisation that has the right to determine who participates each year.

I think that we can read between the lines that there would most likely be immense pressure for the Board to rethink their initial decision, with the NSW Premier and other MPs advocating strongly for the police to still be able to march at Mardi Gras.

[Editor’s note: since this piece was written, this is exactly what happened]

I note the loud outcry against the Mardi Gras Board’s initial decision, and I ask people to respectfully reframe from arguments like “not all men”, “not all police officers” and “it is just one rotten egg”.

This is deeply unhelpful during this time and works to undermine the hard fought for feminist and anti-oppressive understanding that violence stems and is maintained by systems and institutions. It also distracts from what is needed now, a serious inquiry into policing and their attitudes and responses to the LGBTQA+ community.

I want to be clear that a discussion of police marching at any Pride parade is never about individuals in the LGBTIQA+ community being banned from Mardi Gras. Far from it, it is my understanding that every LGBTIQA+ police officer is free to attend and march at Mardi Gras, and that there are hundreds of contingents to be joined and ways to be involved. The respectful ask, as I understand it, is not in their police uniform, and not with weaponry.

In Victoria, I have recently been an expert witness to the Victorian Coronial Inquest into the deaths of five transgender women. This enquiry has unearthed police abandonment of care, policy failures and lack of understanding of the Transgender community, and how this directly impacted the search for Bridget Flack in the days following her going missing and later found dead due to suicide.

Tragically, there is a thread through from the murder of Jessie and Luke to the recent coronial enquiry, that is driving an ever-greater wedge between police and LGBTIQA+ communities.

This moment calls for us all to increase our understanding of gender-based violence, where it comes from and accordingly what role we can play in our own lives to prevent it.

In Australia, according to the community register Counting Dead Women Australia, 10 women have been killed already this year, up to 21 February, due to gender-based violence. Luke and Jessie add to this toll as people killed by men’s violence. Any person or persons killed in an act of gender-based violence must be treated with respect.

And where there are systems failures, including in policing, we must demand enough, in one voice.

Finally, we cannot discard the serious concerns many in the LGBTIQA+ community have with police. These murders compound the distrust that already exists and puts LGBTIQA+ lives at risk, because this distrust can lead to LGBTIQA+ people not turning to the police when they need them most.

—

This article was first published by Croakey Health Media under the title ‘Navigating tragedy and accountability in the wake of Jesse Baird and Luke Davis’s deaths’ republished generously with their permission:

About the author

Joe Ball is CEO of Switchboard Victoria, a community-based not for profit organisation that provides a peer-driven support service for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and gender diverse, intersex, queer, asexual (LGBTIQA+) communities and their allies, friends, support workers and families.

Some of the services they provide include seven-day-a-week LGBTIQA+ helplines – Qlife run in partnership with other state-based services, and Rainbow Door which is a Victorian LGBTIQA+ helpline for the prevention of suicide, family violence and to support mental health and wellbeing.

Further reading:

Revisioning – https://thorneharbour.org/services/relationship-family-violence/revisioning/

No to violence – https://ntv.org.au/

The media exploited Beau Lamarre-Condon’s homosexuality when reporting on the murder of Luke Davies and Jesse Baird - https://heterosexualnonsense.substack.com/p/the-media-exploited-lamarre-condons