Even though I am a fancy boy, I am not worried about the zombie apocalypse! The Last of Us does not scare me.

if the zombie apocalypse comes, do not beep me, I am not going to engage!

Welcome to our new All The Heterosexual Nonsense column, which is called Stupid! With Patrick Lenton, a fortnightly newsletter exploring the intersection of pop-culture, comedy, and queer stuff.

For a very long time I have claimed that I am not a horror girly, that I am not going to engage when it comes to the spills, chills, and especially the thrills. Films like M3gan and shows like Stranger Things are probably the limit of what I can handle when it comes to the spooks.

It’s the tension that I don’t like – the build, the anticipation, the weaponising of anxiety. I have an anxiety disorder, I get heart palpitations just from turning right in my car, I don’t need to be manipulated via narrative into feeling this kind of fear and tension. Even though people talk about the cathartic effect of the moment after the scare, the “fear cum” moment, to put it awfully, I simply cannot be bothered to go through all that. Yes, I could have the dizzying high of horror film catharsis, or like Des’ree once propositioned, I could simply have a piece of toast instead.

Despite not playing the game (I may not be scared of the zombie apocalypse, but that doesn’t mean I want to actively engage with it on a console), I was very excited about The Last of Us, the new zombie apocalypse HBO show.

The strange exception to this horror rule is that I am an absolute slut for the zombie apocalypse. It does not scare me.

The scariest thing about the zombie apocalypse is how slow everyone walks. Move faster, I am queer!

Zombie apocalypse narratives shouldn’t all be categorised as being thematically similar, but I think it’s fair to say that the classic inspiration for the genre comes from anxiety about societal collapse.

The zombies are manifestations of the rapacious nature of people, of our neighbours, when something breaks in the fragile system of law and order that we rely upon. It was interesting, during the peak days of the covid-19 pandemic, to actually see how tenuous some of these societal foundations are, in exactly the way that these zombie narratives project.

This is manifested all the way from classic zombie films like Night of the Living Dead, all the way to more recent incarnations like 28 Days Later, The Walking Dead, and most recently The Last of Us. The focus has shifted too - whereas Night of the Living Dead focuses on the horror of zombies arriving and fucking everything up - whether from radioactive space probes or mutated viruses - more recent narratives have settled in the consequences, the years after the collapse, the reality of life post-society. Living with the virus, to borrow a term. It’s the difference between a zombie thriller and a post apocalyptic film.

The Last of Us, for example, begins its pilot episode on the night before the contaminated fungus that makes up the zombie origin story in this world (from what I understand, the evil fungus spores got into wheat crops? i’m gluten intolerant, so I would probably have been fine). The Walking Dead, now in its 11th season, with spinoffs, has now theorised several iterations of post-apocalyptic society.

The fear of society collapsing is a potent one. I think it’s also a fascination, perhaps a seductive one for many people who don’t particularly love the cards that society has dealt them. While the zombie apocalypse is bad, so is capitalism, so who can really say if a bunch of suits from the stock market being eaten is that terrible?

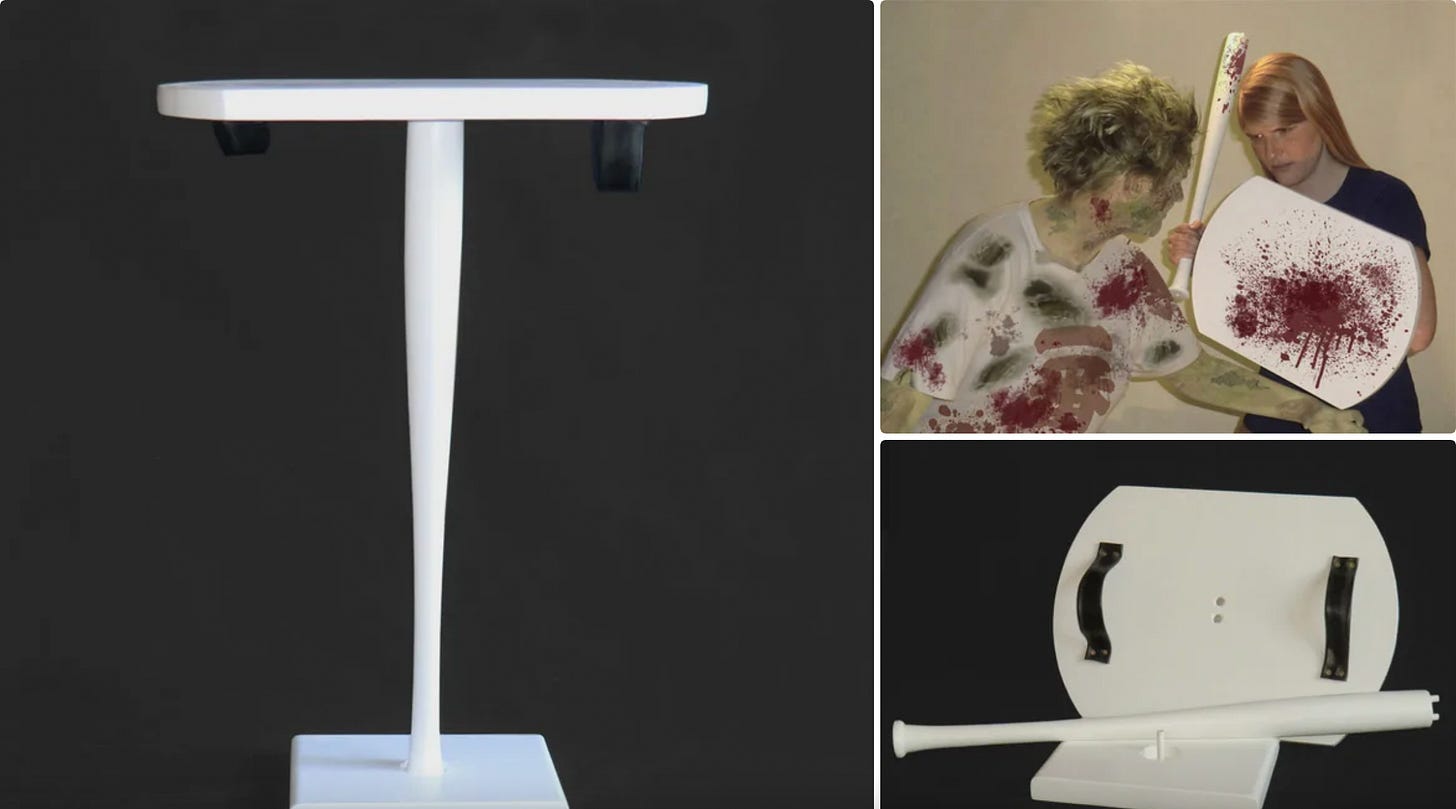

This obsession is such a potent one that it not only explains the continued success of zombie apocalypse narratives, it has spawned entire sub-genres of preppers who have specialised in zombie based anarchy preparedness. I remember in the 2000s height of the genre, around the peak of The Walking Dead, films like Shaun of the Dead, and books like World War Z, games like Resident Evil, there were often viral zombie preparedness things, such as a bedside table which turned into a zombie-killing bat ensemble.

I shall never pickle

The reason I am not scared of the zombie apocalypse, and can watch these shows with relish, like I am the bravest big boy in the world, rather than a filthy coward, is because of a realisation I had after consuming way too much post apocalyptic narratives and going a little insane.

I can sometimes get a little hyper-fixated on narratives, and as my primary school report cards always stated, I have a “wild imagination” which was then usually followed up with “daydreams too much”. During a binge session of The Walking Dead, reading a bunch of zombie books (including the wonderful Feed series by Mira Grant), which corresponded with a stressful real life health situation, I started inching down the prepper road. I suddenly realised how tenuous the things that were keeping me safe in society were, and how unprepared for literally any situation I am, unless it’s “looking hot at the dickhead factory”. Unless writing a tight sentence is somehow useful, I might be the most unprepared man in the entire world when it comes to the apocalypse.

I began researching things like canned food hoarding, which is more complicated than you might think. I created a “go bag”, which had good intentions, but ended up looking more like the knapsack on a stick that a tiny child takes when they declare they are running away from home, just a bunch of weird trinkets and a muesli bar. I began thinking about where I would flee – a farm? An island?

This kind of proactive attitude towards my own spiralling anxiety is not out of character for me, such as the time I got very upset during the marriage equality survey era and signed up to a whole bunch of martial arts training so I could beat up homophobes. I started thinking about my prospects as a survivor – I’m not strong, or smart, or quick, or fit. I don’t know anything about farming or fighting or pickling or hotwiring a car. At the time I was running a small independent theatre company, and wrangling a bunch of actors and creatives using sheer force of will alone - perhaps my only chance at survival would be to somehow bamboozle a bunch of actually capable people into protecting me, using my skills as a volunteer arts administrator. We could fight zombies by day and also tour a production of Cabaret by night.

But the more I thought about it, the more I immersed myself in bunker theory, the more I started to wonder about the point of it all.

I would rather die than live in a world without martinis

In season 1 of The Walking Dead, the group of survivors we are first introduced to have basically set up a camp site near a quarry, up in the mountains outside of the city. There’s a camper van, a bunch of tents, they gather around the fire every night. The scenes of everyday zombie apocalypse domesticity, washing clothes in the lake, hunting for food, corralling the children, are punctuated by the more violent adventures that TV tends to focus on, the bashing of the zombie brains, the horrifying horse deaths, the high stakes bean collecting. While, in the moment, I’m obviously more scared of the flesh eating undead corpses, I found myself looking at the situation of never-ending camping and realising that for me, this is the truly horrific situation. A lack of hot water and flushing toilets? This is the true apocalypse.

I famously hate camping. The last time I really pushed myself to try was at a music festival, and after a night of horror in a stinking hot tent, leaking water onto my face, my legs sticking out the flap into the mosquito-ridden air, I told my friends that my grandma had died and caught a bus to Brisbane airport and flew home.

Likewise, in The Last of Us, we’re given a look at what society has turned into around twenty years after the initial zombie outbreak. It’s a military state fascist dictatorship, with the military using the (very real) fear of zombies and societal breakdown as a way of exerting complete control. It’s equally awful. Seeing both incarnations of society, my overwhelming instinct was “I’d prefer death”.

I adore my comforts. I love my fripperies. I have often thought about how awful it would be to travel through time with the Doctor and continually end up in the past, before the invention of sewers, where everything smelled like shit and piss. I’m a fancy boy, who has worked very hard to be in the position where I don’t have to do anything I don’t like: experience the discomfort of the elements, eat beans, touch the dirt, age at a normal rate, have dry skin. I’m a sickly boy, a slaved to vaccines and antibiotics and various ointments, all of which keep me alive. Take any of those away, and the suffering begins. I don’t want to suffer.

I realised that my minimum level of comfort in life is having hot water to shower, and ice to make cocktails. Anything other than that, I’m not interested in being involved in. I would simply throw myself to the zombies rather than endure an uncomfortable world. I would fire a crossbow into my beautiful brain. I would throw myself off a tall tower.

Once this epiphany occurred, the terror of these shows simply ebbed away – I don’t have to worry about the zombie apocalypse, because I simply refuse to engage with it! I would not even try to survive. I refuse to endure. Now that I’ve decided I can’t live under these conditions, it turns these narratives into an interesting hypothetical, as effective as someone else describing their nightmare to you.

Much like my dislike of horror in general, I have realised it’s the discomfort that the zombie apocalypse would bring that is my dealbreaker.

There is a fundamental difference between the horror of the zombie apocalypse and the type of horror in other films, which I remain a big baby about, which I am still terrified about. I am not scared of the zombie apocalypse now, because I am not tortured by the hope of surviving it - or more pertinently, that I don’t want to bother surviving, because that world is so joyless. I don’t want to live in it. Whereas in another horror film - a serial killer slasher, a spooky paranormal, a psychological mindfuck, the real world that I love still exists outside the confines of the haunted house or death factory, will still be there if I am able to escape from the killer. The hope that I, or the character we are engaged with, will survive, still exists - and that’s terrifying. I am too invested not to be scared. Hope is the epitome of investment.

But the zombie apocalypse? I have relinquished all hope, so I’m not worried.

What does the apocalypse teach us about ourselves?

Obviously i’m being facetious – please don’t point out how shallow and upsetting this theory is, or how many people in the world would be thrilled to live under these conditions, etc etc. I’m aware. I also think that probably I would find that I am a strong person who is about to withstand all sorts of humiliations and discomforts, but also maybe not! And that’s fine. But I do think it’s illustrative of one of the most interesting themes that zombie apocalypse narratives explore: how much we’re willing to endure, and what keeps us going.

In The Walking Dead, the tension between surviving and living is explored as an ethical choice – is surviving at "all costs” worth it? And what does living actually look like. Over many seasons, we see the survivors continually try to put down roots, to create a semblance of quality of life, of community. But we see these stripped away from them over and over again. The core question of the show is “what makes these people different from the zombies” - are they both, in their own way, different types of walking dead?

In The Last of Us, we’re served hope that things can change, in the form of a possible cure or resistance to the zombie fungus disease. I haven’t seen all the show yet, but I imagine that hope is another form of endurance in the zombie apocalypse, a belief that things could get better.

Over and over again these narratives ask how much people can endure. While community, friendship, love and family are seen as reasons to continue fighting and living, the characters are also stripped of them constantly. There are so many deaths in these shows – The Last of Us starts off with one for our protagonist that almost breaks him. The Walking Dead shows multiple examples of people losing the ones they love most in the world, and having to work out how to continue.

It’s also something that the audience experiences - what keeps us watching, what keeps us invested. It can’t just be voyeurism, with delighting in the misery and struggle – clearly we’re involved in that same quest for meaning. Are we looking for hope? Are we finding out what’s important in our own lives (martinis, flushing toilets, hot water) by watching these artfully dirty hotties fight zombies? Or do we just like watching people suffer and bash zombies up?

I think ultimately it’s more than that: in The Walking Dead, there is a notable death in season 7, with one of the original cast members murdered by another human in a particularly gory, traumatic way. By this point, the long-running show had well and truly moved into “shock death” territory, similar to Game of Thrones around the same time, perhaps as a way of dealing with expired contracts, or perhaps because after seven seasons it becomes difficult to think of ways to engage the audience. This death was so shocking and, frankly, disgusting that it fits more into trauma porn than anything else, and its narrative value really only reinforced the bleakness of the world.

It taught us nothing else other than suffering. It exemplified the complete lack of hope that the survivors fear about this world. And it’s clear that the audience felt that too – The Walking Dead lost over four million viewers immediately after that episode, who never came back.

I was one of those lost viewers – even though the zombie apocalypse doesn’t scare me anymore, the idea of watching characters that I’ve been forced to admire and love through narrative trickery (writing) essentially get tortured and die, episode after episode, is not just unappealing, it sounds like torture. In the same way that I won’t put myself through a real zombie apocalypse if it ever happens, I won’t put myself through a hopeless zombie narrative for no reason. The same reason that I would not willingly try to live through a real zombie outbreak, the lack of motives to keep striving, to keep invested – they were exactly the reason I noped out of The Walking Dead. Bleakness, pointlessness, are not terrifying, but they are the death of investment. I’m not scared, I just hate discomfort.

Instead of forcing myself to endure another traumatic death, I will simply make a cocktail full of ice and have a hot shower, and relish the fact that I get to enjoy them.

Thank you for reading! Stupid! With Patrick Lenton is a free fortnightly column – please subscribe if you like this writing and want to support independent comedy culture writers. Our paid subscribers mean I can afford to continue doing this, and I love and appreciate you!

If you are an editor who wants to republish this article, or commission a piece on a similar topic, please get in touch: patricklenton@gmail.com.

I am a giant baby and have not even watched Stranger Things, let alone M3gan, because there is a good chance I would not be able to sleep again for the next 12 years. Aside from iZombie, a few movies here and there, plus one unforgettable for the wrong reasons zombie apocalypse romance book I read for a bookclub once that was hilariously set near Brisbane, I have not felt compelled to partake in anything Zombie. I think a combination of not liking a lot of gore and also see above re giant baby. However, one thing I do know is that in the event of a Zombie apocalypse, I am going out in the first wave. I also famously hate camping. I am not a survivor. I need hot showers. I am very tired. And you are right, there is definitely a peace to be found in this realisation!