I am begging TV shows to ignore fans

And just like that, Che Diaz stopped being a character, and became a way for the writers to yell at their own audience

And Just Like That - a show that can only be described as watching Sex and the City through the aged filter on TikTok while suffering a potentially fatal fever - is the greatest show on television. By that I mean it’s so bad. God I love it. It’s just inexplicably confusing, a show defined by big swings that almost never hit, but that doesn’t matter, there’s a kind of deranged joy in that. It’s almost perfect. But it’s also so weird.

There seems to be a happy chaos to the show, a willingness to just put forward insane new developments for these beloved characters, and just run with it. If you’ve seen the final episode of season 2, then you’ll understand why I was running around the house screaming “five years! Five years???”.

But, just like Sex and the City did so well, amidst the shenanigans, amongst all the attention-grabbing sex and to a lesser extent, the city, And Just Like That often pulls real moments from the insanity - the conversation between Seema and Carrie outside a hair salon wasn’t revolutionary, but felt real and fresh, a moment of domestic, every day truth given air, and explored in a way that felt both authentic to the characters, and firmly set in SATC’s original mission statement of depicting the lives of women in the big city.

The exception to both these types of narratives in AJLT - the bonkers and sporadically brilliant - is the character of Che Diaz in season 2. And the reason that Che Diaz felt so out of place, a sore thumb, is because their entire arc in the latest season is responding to fan and critical discourse. And that’s just bad storytelling.

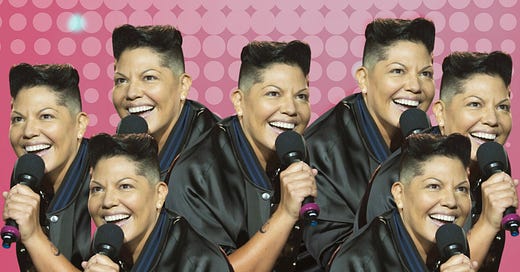

Hey, it’s Che Diaz

Che Diaz in season 1 was possibly the exemplification of the insanity of this revival. Introduced as Carrie’s “modern” podcast partner, and then later Miranda’s queer sexual awakening, Che was a non-binary standup comedian who unfortunately had a lot of functions to fulfil in the story. They were a kind of stand-in to represent exactly everything that had changed in sex and dating and gender and sexuality in the years since the original Sex and The City had gracefully left our screens.

They were quickly deemed insufferable by the audience, and turned into a multitude of memes. In their first scene in season 1, Che welcomed their two cisgender co-hosts onto the podcast by calling Carrie “Ms. Cis,” introduced themselves as a “queer, nonbinary, Mexican Irish diva representing everyone else outside these two boring genders,” and then they ACTUALLY hit a button on the soundboard that screamed “WOKE MOMENT!” I remember watching this scene and wondering if this is what passed as right-wing parody.

They were a truly baffling character, a kind of frankenstein’s monster cobbled together from hazy ideas of gender and queer theory, mashed into one character to be a comedic foil for the older (and somewhat startlingly conservative at times) original characters - but also as a way to try and seriously engage with ideas of representation and diversity. You never knew if you were meant to laugh at Che, or at the other character’s moments of less-than-wokeness around Che - or take them seriously. And Che wasn’t the only vehicle for this - in the first season we also had Charlotte’s child, Rock, exploring a non-binary identity, as well as Miranda leaving her husband and exploring her, as of yet undefined, queerness. The show really decided to go all in, but it felt like it was doing so with all the care and consideration of a dog chasing a tennis ball across a busy road.

Much of the mockery towards Che came from the queer community, who were pretty easily able to see the difference between an authentic representation of a queer character, and a kind of walking diversity checkbox designed to bring a style of woke chaos to a story. It wasn’t Che’s fault that they were insufferable, or the fault of Sara Ramirez who plays Che - they were burdened under the weight of representing an entire social movement, the progress of sex and gender over the last few decades, and every feeling of unease that occurs between the perceived split between the demographics of the original watchers of the show, and the new, younger audience.

That’s a lot for any one being to labour under, and it’s no surprise that they came across as more of a caricature of a queer person than a developed character. But, as much as I also found them hilariously terrible, ultimately I felt that they were a kind of avatar for the weird decisions in general that the show was taking.

It’s still Che Diaz

In the first season, it wasn’t entirely clear WHY they decided to top load Che Diaz with the burden of representing progression. The theory I had at the time was that social mores were always the bread and butter of Sex and the City, and they felt that thematically this would be the world the original characters now navigated.

This is probably partially the case, but it’s clear from what they did with Che in the second season of AJLT that much of the motivation for creating the terrifying queer homonoculus that is Che Diaz was defensiveness. Since Sex and the City has been on the air, it’s been the grist for endless cultural critique, which has meant that its been retroactively judged for how it currently meets today’s ethical standards. It’s pretty common - legacy shows like SATC or Friends are often found wanting - it is astonishing to watch the Monica fat-suit episodes today. AJLT has clearly been engaged in the criticism of SATC - the three main characters all get a black friend who is given almost equal time and importance. And Che not only answers criticism of lack of representation of sexuality on SATC, but cuts off future criticism of AJLT.

Che Diaz is not a character, they are a defence mechanism against fan and critic judgement and ultimately, against the threat of cancellation.

In AJLT season 2, that defensiveness kicks in around Che Diaz, but this time it’s about the response to season 1. Che is definitely given more depth and time as a character in their own right - they are no longer accessories for Carrie or Miranda. But it’s clear that the motivation for doing this isn’t because the character has narratively grown - it’s because the show is incredibly sensitive to the response to Che, and are making a point to refute the criticisms, and to forestall future complaints. Good try! But the terrible goblins of the culture critic world will always find something to pick at.

Che Diaz in season 2’s major arc is the sitcom pilot they are doing with Netflix, Che Pasa. Through this, we get the metatextual experience of watching the character of Che Diaz create another Che Diaz character in the show - and use it as a way to not only try and resolve criticisms of Che Diaz in AJLT, but to scold the audience for those savage disparagements.

In one scene, Che is watching a focus group give feedback on the pilot of their sitcom. A young, clearly queer member speaks up about how much they hate the “character” of Che in the sitcom. They clearly represent the fan and critical response to Che Diax in AJLT season 1, and it’s fascinating to see what the show thinks these kinds of people are - ie a minorly updated blue haired woke stereotype.

“It sucked” is how they describe Che’s character, saying it is a “phony, sanitized, performative, cheesy-ass, dad-joke, bullshit version of what the nonbinary experience is.”

This is a handy summary of the criticisms the real world had of Che too.

In the show, this brings Che to tears, and through this scene, our criticism of Che is emotionally rebuked. We can see that the tears of Che Diaz are the tears of the writers, appalled at our meanness.

“A genderqueer person from Brooklyn tanked it! That call came from inside the house,” says Che, after Miranda tries to console them.

The way this storyline is constructed clearly places Che as the victim in this situation - but more importantly, is designed to show those criticisms as being mean-spirited and lacking in empathy for the supposed authenticity of Che’s non-binary POV.

If it wasn’t clear that the show’s writers were speaking to the critical response directly, the incredibly defensive response from actor Sara Ramirez to a profile of them in The Cut, called Hey, It’s Sara Ramirez, proves that the critical response has been noted, and has affected them.

“Been thinking long and hard about how to respond to The Hack Job’s article, ‘written’ by a white gen z non-binary person who asked me serious questions but expected a comedic response I guess,” Ramírez wrote in a post that included two photos that had been featured in The Cut’s story, but didn’t name the reporter directly.

The way that this response is essentially the same as the fictional Che Diaz is both fascinating, and proof that all of Che Diaz’s narrative choices in season 2 were motivated by butthurt defensiveness over discourse happening in fan and critical spaces, which is why it feels incredibly uncomfortable to watch. Nobody wants to feel chided when watching a TV show.

Fandoms are the opposite of good storytelling. We need to stop pandering to them

In the case of AJLT season 2, the influence of fandoms and the fandom apparatus - I’m including critical response, such as articles and podcasts and youtube videos in this, because it’s often the only lasting ways we see discourse manifested outside of fan spaces - is easily seen. They were able to affect the tv show, affect how the art is manifested, how the writing is structured, the choices the character makes - purely through the opinions. It gives a lot of power to fans.

And I think that’s a bad precedent! It’s a kind of tail wagging the dog situation, because fans are always going to be motivated by different things to the writer. A fan, especially ones with the kind of parasocial relationship to shows and characters that are big these days, are always going to want the best for the character, to see their favourites thrive and find love and get the magic sword, etc. A writer doesn’t and shouldn’t care about any of that - a writer should only be writing the best story, creating the most fulfilling narrative arc. Sometimes, when it comes to crafting a narrative, pain and suffering is important for the character, goals need to be unreached, swords remain in the stone. Otherwise we’d have no story - a narrative is often easily condensed into the hurdles that stop a character from reaching their goal, and the things they learn as a result. We wouldn’t have a show if there was no struggle, no hurdles. We’d just have people sitting around.

But in AJLT’s case, it feels less like the writers are trying to appease their fans, but are rather expressing their own dissatisfaction with them. The entire show feels like it has a chip on their shoulder, a weary exasperation at the indignity of being perceived by these people.

I also think in this case they might be making a demographic play - the original fans of SATC catered for, whereas the new hypothetical breed of hyper-woke youth treated with distrust. Woke moment!

Storytellers need to make the firm decision to remain unbent and unbroken by the thoughts and opinions of fans - and most importantly, make sure none of it affects the story they are writing. But this has become much more of an issue, as fandoms grow in power and influence.

How dare you kill my best friend, Eddie Munson

After the character of Eddie Munson heroically died helping defeat the evil Vecna in the recent Stranger Things season 4 volume two, social media was awash in reactions – videos expressing sadness at his dramatic death or glorifying his sacrifice, exceptionally horny memes about the actor’s kind smile and fabulous 80s mullet. But along with the relatively normal set of reactions, a large portion of people took Eddie Munson’s death a further step forward - not content to simply be sad at a fictional character's death, but to be angry, appalled, and most of all, outraged.

On Change.org, a petition quickly popped up “kindly asking Netflix and the Duffer Brothers to bring back the fan favourite character Eddie Munson”, claiming that he was “ unfairly killed off”. It currently has over 83,000 signatures. The petition, to many, is probably just a bit of fun, a way to vent some emotional steam after being deeply invested in a show and its narrative. But comments on the same petition show that there’s some deeper anger behind it all for many.

“killing him was probably the worst decision you could’ve made and i hope u suffer like we do because of it,” wrote one of the signees on the petition.

It’s this fan feeling of “unfairness” that has become something of a trend – with engaged fandoms feeling a sense of outrage at decisions made by writers and showrunners, a feeling of entitlement to how their favourite characters are “treated”, and overall a sense of suspicion about tv and film narratives. It could almost be seen as a kind of “us versus them” mentality, with writers cast as arch-manipulators, and fandoms as the champions of the soul and purity of the show. We could also say that the reserve is true - as AJLT shows, sometimes the writers feel attacked by fans.

This often manifests not just through outrage, and anger, but cultural criticism spoken through a lens of appropriated social justice terminology: Eddie’s death is not just unfair, it is problematic. One popular TikTok video posits his death as anti-semitic – another says that because his character is “queer coded” that the Duffer Brothers are homophobic.

Reactions to character deaths are nothing new – from Molly’s death in A Country Practice , to the TV event that was the tragedy of Marissa Cooper's death in The OC, they’ve always been big moments for viewers. Fandoms often take it a step further however - there’s still a shrine in Cardiff to Ianto from Torchwood. Due to the power of social media, fandoms do have a lot of power, and have successfully used their collective anger to implement change. There are plenty of examples of shows angering their fandom to such an extent that their own viewership has turned against them - after BBC’s Robin Hood killed off the character of Maid Marian in the second season, the show was flooded with complaints, leading to the resignation of show’s co-creator and one of the writers of that episode, and such a huge ratings drop that the show was cancelled. After Loki's death in Avengers: Infinity War, fans flooded Marvel's social media accounts to the point that The Russo Brothers admitted that they had to temporarily withdraw from social media to avoid fans' wrath, with their page on Wikipedia repeatedly edited, with "murderers" being added to their occupation list.

After the sudden and shocking death of the character Will Gartner, The Good Wife creators Robert and Michelle King actually took the time to write a letter to their audience, explaining that while they mourned his death too, they chose to do it for good storytelling. It was essentially trying to get ahead of the outcry.

“Death also created a new dramatic ‘hub’ for the show”, they explained. “We’re always looking for these turning points — some event midway through the season that will spin everybody’s lives in new directions.”

Like we love fandoms, but we just don’t want them ruining the shows they love by loving them too much

Huge fan-led campaigns have also saved their shows from cancellation - such as with Brooklyn Nine-Nine or One Day at a Time. This power to affect the narrative of shows is extremely troubling – while it comes from an undeniably exciting place for a tv show or franchise, deep and committed investment by viewers, it’s also an attitude antithetical to good storytelling. A fandom, by its nature, is more invested in wish-fulfilment than narrative arcs.

This suspicion on behalf of the fandom isn’t necessarily delusional however – some of it comes from the inherent emotional manipulation of a good narrative - but there’s also an element of audience getting wise to flashy, gimmicky storytelling.There’s an easily traced legacy from that show specifically around character deaths that still influences us today. Game of Thrones made TV history when it deliberately subverted the hero's journey style trope familiar to most fantasy narratives by killing off its top-listed actor (Sean Bean as Ned Stark) in the first season. In later seasons of the show, it could be said that characters began to be killed off not to meaningfully advance the plot, but rather to continue getting those big audience reactions, to create “shock value” deaths. Audiences have since been trained to expect and fear that every season finale of a show will also feature a beloved character being murdered for reasons not inherently linked to narrative.

There’s also a broader knowledge in viewerships about bad decision making behind the scenes of the show which can impact narrative. Practices such as queerbaiting, where films and TV will actively try to recruit LGBTIQ audiences with promises of queer representation or romances, but fail to actually manifest these in the plot of the story, actively cause fandoms to second-guess the motivations behind certain plot choices. Another example is the “bury your gays” trope – an extremely common narrative device where queer characters are introduced only to be killed, or given happiness only to be murdered as a result.

When actors from Thor: Love and Thunder spent the entire marketing push claiming that it was Marvel’s “most queer film yet”, yet only delivered a weirdly chaste scene of two homosexual rock-aliens getting married over a lava vent, a queer audience is validated in looking behind the scenes for evidence of other manipulations.

The massive outcry about the death of Lexa in The 100 (immediately after being given a lesbian relationship) is often considered the flagship example of the trope, and can be seen as informing much of fandom’s relationships to the shows they love.

Along with the outcry about Eddie’s death, there was a similar level of unhappiness from many in the Stranger Things fandom about supposed “queerbaiting”, including accusations of homophobia towards the show. In season 4, Stranger Things begins explicitly telling a story about a closeted Will Byers trying to come to terms with his sexuality, as well as an unrequited crush on his friend Mike. It’s an inherently queer story, and also realistic for the eighties. However, the fandom having picked up on this plot, actively campaigned for a “happy” ending between Will and Mike.

Much of the evidence used by fans to support their sense of outrage comes from the apparatus around the show, rather than in the narrative - interviews with cast, marketing, hints and teases over social media. For a generation of fans already suspicious, already trained to pick up on easter eggs in massive franchises, can you blame them when the Stranger Things twitter account uses fan terms like “Mileven”, referencing the relationship of Mike and Eleven, pandering directly to the most capricious and emotional portions of the fandom?

Likewise, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has seeded their films with so many “easter eggs” or clues, to both help tell a broader connected story and to help promote other films in the universe, that fandoms have begun treating narratives as something closer to a crime to unravel. As a result, fan theories such this Reddit user who wrote an an entire essay explaining how the use of Metallica's Master of Puppets and Siouxsie and the Banshees' Spellbound in the finale foreshadows Eddie coming back as a vampire, are extremely common and popular.

Fandoms have become monstrously powerful and influential, usually for all the wrong reasons, but much of the blame for that has to come from the shows, networks, films and entertainment bigwigs who actively pander, entice, and capitulate to them. For everyone's sake - including the fans themselves, although they might not realise it - we need to ignore fandoms and focus only on telling the best stories we can.

In season 3 of And Just Like That, let’s hope that Che Diaz is given an arc entirely separate from the burden of expectation, defensiveness - and maybe even cringe?

—

Thank you so much for reading ALL THE HET NON. We love you. We pay each of our writers, and rely on our subscribers to do that - please considering paying to subscribe and helping us platform cool writers.

As bad as this pandering is, it could always be worse - Mass Effect 3 released a patch permanently changing their ending in response to fans campaigns (and other games have followed suit). Given we've already seen shows edited to suit censorious markets, we're probably not too far off from editing for fan reasons as well.

Thank you, Patrick; this piece is perfection... I loved SATC. It was perfect and did not need two movie follow-ups and a sequel. I want to see new TV shows with writing as good as SATC, and authentic representation that reflects real people. I do not want cringe sequels written poorly and produced by networks trying to relive something that once was. Rant over